Dr Liisa Ahlstrom, explaining how to apply SerestoTM for Dogs, the only product that reduces the risk of transmission of ehrlichiosis.

Four years after its initial discovery in Australia, canine monocytic ehrlichiosis (CME) continues to cause illness and losses of dogs in remote regions and indigenous communities and is now widely disseminated across northern Australia. Worryingly, and as originally predicted, CME is diagnosed with increasing frequency Australia-wide in dogs that have travelled to the north, returning home infected to southern regions.

CME is caused by the rickettsia-like member of the Anaplasmataceae, Ehrlichia canis (E. canis), is transmitted by the brown dog tick Rhipicephalus linnaei (recently renamed from R. sanguineus). Prior to the first cases being discovered in Kununurra, in the Kimberley region of WA, in May 2020, the Australian continent was considered free of the disease. Strict pre-import testing of dogs coming to Australia for CME had served the country well until this incursion. In December 2023 CME was removed from the national list of notifiable diseases in Australia, however some states and territories still require cases to be reported to veterinary authorities when a case is diagnosed. Vets should check with their local authorities for up-to-date information about their reporting obligations.

The disease is still most prevalent in regional areas and remote communities, where the ability to test dogs is restricted, and veterinary workers report that dog populations in some communities have been decimated.

Canine ehrlichiosis is a life-threatening disease for dogs and represents the most serious threat to canine health in Australia since the parvovirus outbreaks in the late 1970s and 1980s. Veterinarians throughout Australia should be very concerned about this disease, not only because of its welfare implications, but because CME will now have to be included on the differential diagnosis list for many medical problems in dogs, ranging from unexplained fever, bleeding diatheses and bone marrow disease.

Ehrlichiosis poses a serious threat to the health of dogs in Australia.

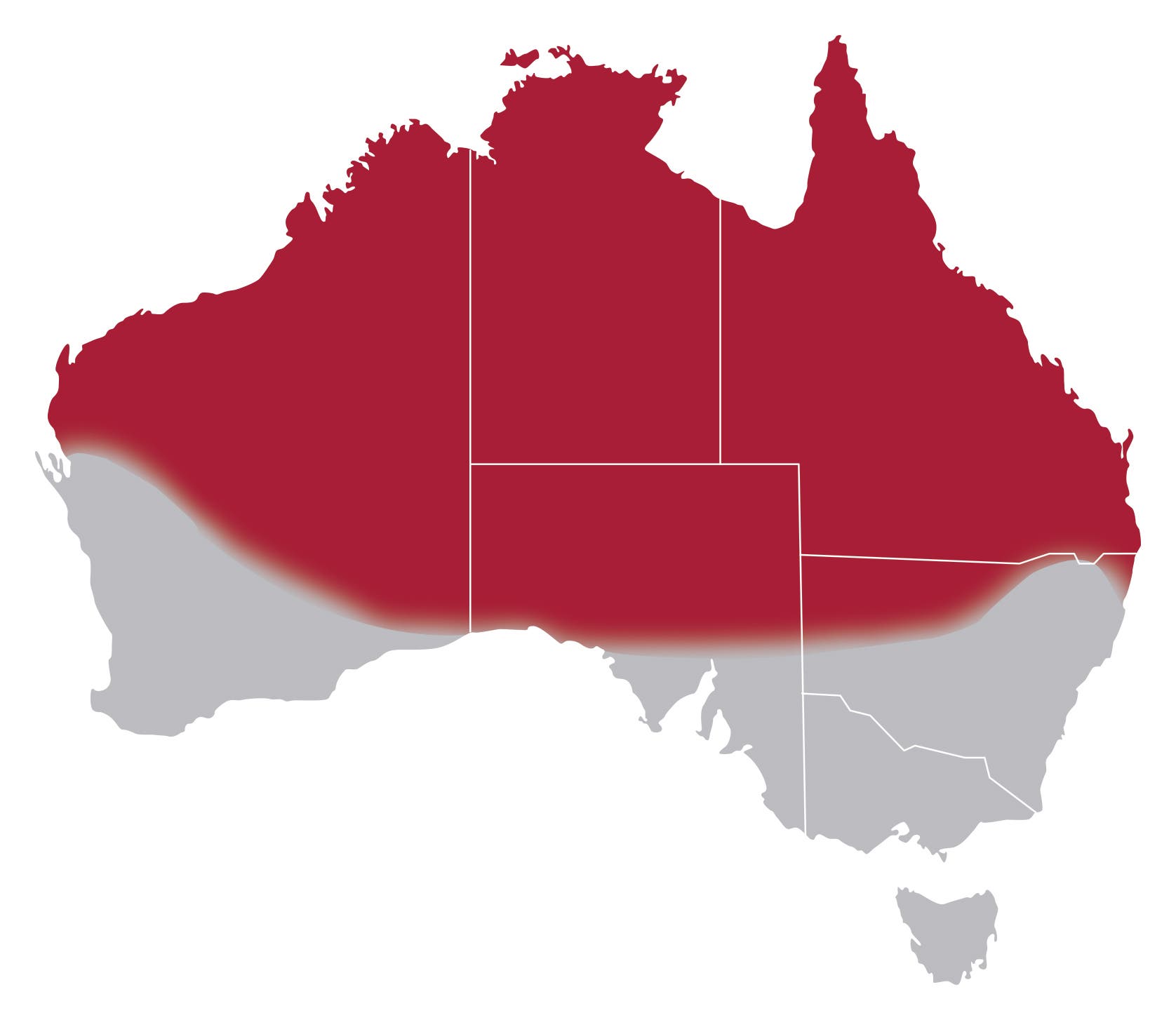

Recent research has confirmed not only that there has been a southwards expansion of the brown dog tick’s geographical range over the last 20-30 years, but also that the brown dog tick strain here – R. linnaei – has been proven to be the most effective and capable strain for maintaining the life cycle of E. canis. Worse, the tick is also well adapted to indoor living and readily establishes within kennels or homes, and even in cooler climates.

Brown dog ticks occur throughout the red shaded area of Australia but can also survive within houses and kennels in colder regions. Map adapted from Teo et al., 2024. Int Journal for Parasitol. 54:453-462.

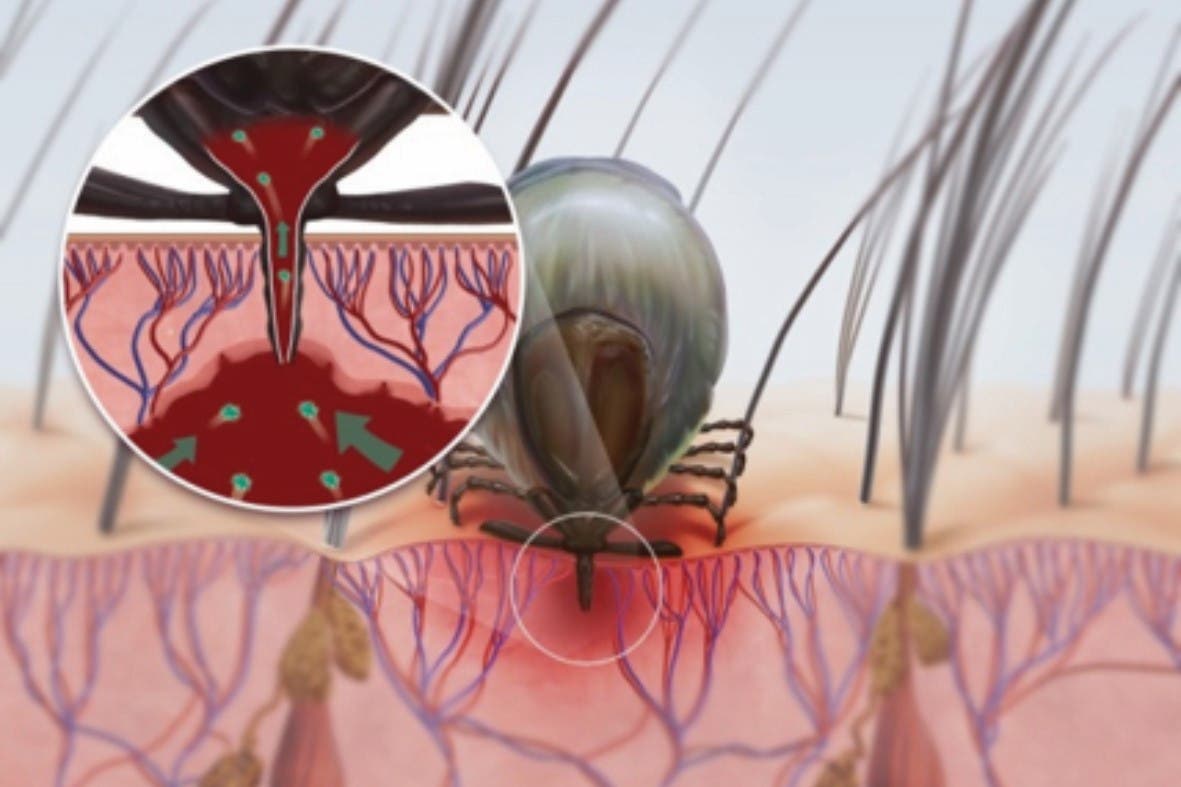

Historically, E. canis was first discovered in the 1930s, named then as Rickettsia canis due to its close relationship with the rickettsia group of bacteria. However, the disease it causes first came to the attention of veterinary scientists worldwide as ‘canine tropical pancytopenia’ during the Vietnam War, when scores of United States (and other nationalities’) military working dogs, often German Shepherd dogs, were infected and died in southeast Asia. The life cycle of this vector-borne disease commences after E. canis bacteria are released from the tick’s salivary glands and injected into dogs very early, within 3 hours, of tick attachment. Indeed, this is a critical fact with respect to preventing dogs from becoming infected as we discuss later in this article. Ehrlichia canis enters the bloodstream and is taken up by monocytes where it multiplies rapidly, spreading throughout the body, and causing clinical signs that are first observed about two weeks after transmission.

Early stages of the disease – the acute phase – are characterised by fever, anorexia, lethargy, ocular signs (conjunctivitis, corneal oedema, uveitis), and bleeding tendencies, such as nose bleeds and widespread petechiae. Some dogs develop severe and rapid weight loss, swollen limbs, difficulty in breathing, blindness and neurological signs. Dogs that survive this stage of infection progress to a subclinical phase that can last many months or even years. This is a concern for several reasons; first, persistently infected dogs that do not receive adequate tick prevention can continuously spread E. canis bacteria to the next life stages of biting ticks (i.e. nymphs or adult ticks). Secondly, dogs with long-lasting E. canis infections may develop illness at any stage, and chronic infections are harder to diagnose as a result of intermittent bacteraemias, and E. canis organisms sequestered in the spleen or bone marrow, for example, thus evading detection by PCR (see later).

One of the most serious, chronic phase effects of this disease in the canine patient, is on the bone marrow with a frequently fatal outcome. Dogs die of septicaemia as they can no longer fight off even the most innocuous of infections, or they bleed uncontrollably.

The spread of CME across the north of Australia has unique epidemiological features that likely combine to explain why the disease has been so devastating. First, there is a well-established population and limitless reservoir of brown dog ticks across all of the Top End. Ideal climatic conditions combined with patchy ectoparasite control in indigenous communities result in very high tick densities. And lastly, and perhaps most critical of all, is the immunologically naïve dog population with respect to E. canis.

Vets in northern Australia are well used to diagnosing tick-borne diseases, notably anaplasmosis (Anaplasma platys infection) and babesiosis (Babesia vogeli), together with other tropical diseases such as hookworm infections that present them with challenging cases to treat.

Infection with E. canis results in systemic inflammation that is often severe and sustained. Host’s immune responses are predominantly B-cell mediated, resulting in large amounts of circulating antibody. Not only is this antibody non-protective, immune-complex formation causes widespread secondary immunopathology, such as vasculitis, uveitis, glomerulonephritis, and hepatitis. Anti-platelet antibodies cause platelet destruction, and hypergammaglobulinaemia may contribute to reduced platelet function (thrombocytopathia).

Clinical suspicion for CME should be increased in dogs with recent tick or travel history, in dogs with pyrexia and the other clinical signs mentioned previously, or in dogs with unusual haematological and biochemical disturbances. Thrombocytopenia is the most common abnormality on a CBC, however anaemia (regenerative or non-regenerative) is also commonly reported, as is bicytopenia or, in some cases pancytopenia, raising concern about bone marrow failure. As noted above, multiple organs may be affected, reflected by respective serum biochemical abnormalities. Hypoalbuminaemia is a common finding, as a ‘negative acute phase protein’, and often accompanied by hyperglobulinaemia. Most cases of CME have elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations.

A confirmed diagnosis requires specific testing that demonstrates the presence of E. canis in the sample being tested (usually blood). This is achieved most readily by PCR, available from most commercial and some state-run laboratories, sometimes as part of a “tick-” or “anaemia” panel that includes PCR for other vector-borne pathogens at the same time. Serology is also offered by laboratory services and may be helpful in some circumstances, although cannot distinguish between current and previous infections. Antibody titres to E. canis are long-lasting (months to years), even after successful treatment, so this requires careful interpretation. Finally, the value of a blood smear examination should never be overlooked; not only is this an essential component of in-house haematology, but intracytoplasmic inclusions (morulae) of E. canis can be observed in monocytes (occasionally other white blood cells) in acute cases. Take the time to have a good look!

When treated with antibiotics and other supportive measures, most dogs will recover, however some do not respond, and may progress to develop a persistent-to-chronic infection that eventually has a terminal outcome. Doxycycline is the drug of choice and is recommended to be given continuously for 28 days. The literature also reports variable efficacy of doxycycline, especially in more chronic cases, and confirming ‘cure’ has proven difficult in overseas studies. Whilst most dogs will quickly become PCR negative in blood samples, the bacterium may be sequestered in spleen or bone marrow.

Brown dog ticks can lead to heavy infestations, especially in warmer parts of Australia. Photo credit: Olivia Skippings.

In terms of safeguarding pets, studies have shown that E. canis can be transmitted within 3 hours of tick attachment, which is faster than most tick products can kill ticks. The implication for protecting individual dogs is that a tick product that repels ticks, to prevent ticks biting, is critical. Seresto™ for Dogs is a long-lasting, water-resistant collar containing imidacloprid and flumethrin that works on contact to repel and kill ticks, and reduces the transmission of tick-borne diseases, including anaplasmosis, babesiosis and ehrlichiosis for 4 months.* Ticks that come into contact with the hair of a Seresto-treated dog and are repelled will fall off and die, since flumethrin is highly acaricidal on contact with ticks.

Studies have shown that products that work on contact to repel and kill ticks are critical to protect dogs from this rapidly transmitted disease (top). Isoxazolines (in all formats: spot-ons, tablets, chews, injectable) are highly effective at killing ticks, but all require ticks to bite (bottom) and kill ticks too slowly to effectively prevent transmission of E. canis.

However, isoxazolines (afoxolaner, fluralaner, lotilaner, sarolaner) undoubtably have an important role to play in reducing the spread of ehrlichiosis, by contributing to the control of brown dog tick populations. Although isoxazolines kill ticks too slowly to effectively prevent transmission of E. canis from the tick, they are highly effective acaricides that will help break the cycle of disease by stopping an infected dog from being a source of infection for other ticks and dogs in the population.

Finally, are there any implications of this disease for other animals – and humans – in Australia? It would seem that our native marsupials are in no danger from this disease, however the potential impact on dingoes is unknown, and is of great concern. And given the interest in tick-associated illness in humans in Australia, it is worth noting that there have been a small number of reports of E. canis in people in South America.

*Read product label for full directions.