Coccidiosis in poultry: Everything you need to know

Costing the UK poultry industry more than £125.5m annually1 , coccidiosis is one of the most costly diseases in the sector. How can you spot coccidiosis and how can you control it? This article aims to give an insight into the disease, including the causes, symptoms, and preventative treatment methods.

What is poultry coccidiosis and how does it impact birds?

Coccidiosis in poultry is a widespread and highly contagious disease, triggered by parasitic organisms from the genus Eimeria.

Affecting the intestines of birds, coccidiosis can impact in different ways depending on the species involved.

The disease leads to significant economic losses due to its negative impact on bird health and productivity.

The impact of poultry coccidiosis can vary depending on the severity of the infection and the species of Eimeria involved.

Some of the common effects of coccidiosis in poultry include:

- Gastrointestinal disease – The parasites damage the lining of the intestines, leading to:

- Reduced nutrient absorption

- Diarrhoea (which may be bloody in severe cases)

- Dehydration

- Reduced growth and feed efficiency – Poultry coccidiosis can affect weight gain by up to 7%1 due to the damaged intestinal lining affecting nutrient absorption. Broiler feed conversion ratio can also be reduced by up to 10%2

- Weakened immune system – Poultry coccidiosis can put pressure on a bird’s immune system. This makes it more susceptible to secondary diseases such as necrotic enteritis, footpad dermatitis and hock burn

- Mortality – In severe cases, particularly in young or weak birds, poultry coccidiosis can lead to high mortality rates

- Economic loss – Due to mortality, reduced productivity, and increased costs for treatment, coccidiosis in poultry can cause significant economic losses

What causes coccidiosis in poultry?

Coccidiosis begins when birds consume Eimeria oocysts, which are found in dirty conditions such as contaminated feed, water, or litter.

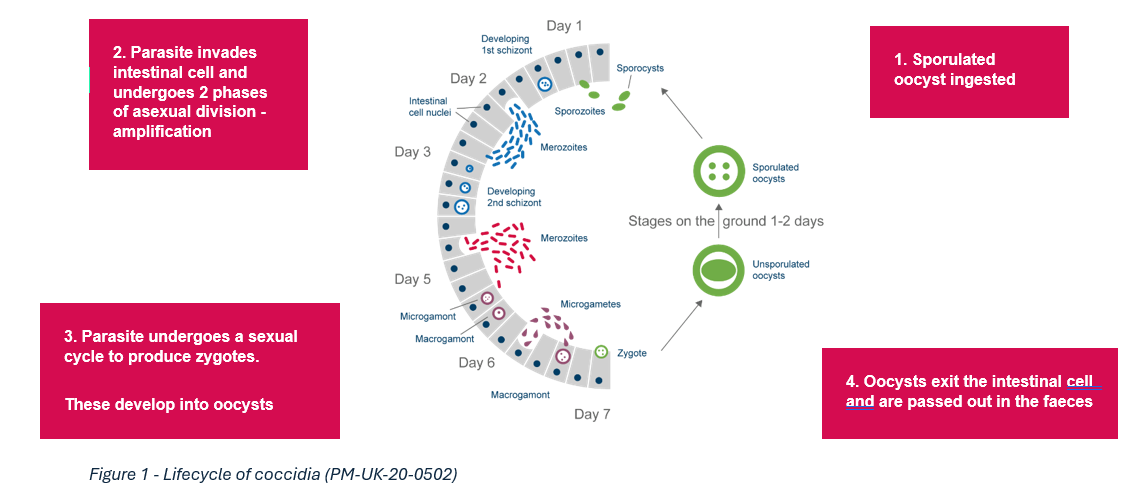

The lifecycle of coccidia:

- Ingestion of parasite eggs: Birds pick up the parasites by eating their eggs, called oocysts, which are spread through contaminated surroundings

- Development of parasites: After being ingested, the oocysts release their contents, which invade the bird’s gut cells

- Reproduction of parasites: Inside these cells, the parasites multiply rapidly producing new oocysts

- Cycle of reinfection: These new oocysts are expelled through the bird’s faeces and go on to contaminate the environment, becoming infective once they mature. This cycle can rapidly infect a large number of birds, especially in crowded or unsanitary conditions

What are the symptoms of coccidiosis in poultry?

Coccidiosis in poultry can be identified by several clinical signs. These symptoms can range from mild to severe depending on the strain of the parasite and the overall health of the infected birds.

The most common symptoms to look out for are:

- Diarrhoea (including bloody faeces in severe cases)

- Wet litter

- Reduced feed intake and subsequent weight loss

- Ruffled feathers

- Pale combs and wattles

- Reduced activity levels

- Dehydration

- Mortality

Mucus droppings

Acknowledging these symptoms early, as well as implementing effective treatment and management strategies, are crucial to control poultry coccidiosis on-farm.

How can you control and prevent coccidiosis in poultry?

The start of the Eimeria parasite’s lifecycle begins outside the bird's body. Oocysts must undergo a process called sporulation before becoming infectious. To infect birds through ingestion, these oocysts require specific conditions, including temperatures above 20°C and sufficient moisture. While conditions are often found in poultry houses, modern technology generally offers opportunities to adapt the environment to help control the parasite.

Sporulation of oocysts can occur rapidly, typically within 48 hours after they’re excreted. Oocysts can persist in the environment for several months or even years, as cold temperatures do not eliminate them.

Implementing strategic cleaning and environmental management practices is essential to control poultry coccidiosis and maintain poultry health.

Effective environmental coccidiosis control measures:

- Thorough cleaning and adequate disinfection after each production cycle

- Ensure the environment is dry before reintroducing birds to houses

- Manage humidity levels and keep litter dry during the production cycle

- General on-farm biosecurity, including boot dips, cleaning equipment and monitoring people coming on-farm

Using ionophores to manage coccidiosis in poultry

Ionophores are widely recognised as the primary control method for coccidiosis in broilers. This is due to their effectiveness, minimal resistance issues, and their role in supporting birds' natural immunity development against Eimeria.

Ionophores, such as Narasin, function alongside the immune system to mitigate the coccidiosis challenge effectively. Many poultry producers have trusted Narasin products for over 20 years without a decrease in effectiveness. This highlights their stable and continuous control of poultry coccidiosis.

Using Maxiban™ in combination with Monteban™ to control coccidiosis provides stable coccidial population control. It is advisable to use Maxiban into and beyond the peak of the coccidiosis challenge and move to Monteban for finishing the birds. This strategic use of both products ensures sustained control throughout the production cycle.

Maxiban and Monteban both contain Narasin, enhancing their compatibility and effectiveness. Maxiban also includes Nicarbazin, and together, these active ingredients work together to manage poultry coccidiosis more efficiently during critical periods of high disease pressure.

Learn about the challenges of coccidiosis in poultry

- Blake DP et al. (2020). Re-calculating the cost of coccidiosis in chickens

- Marusich, W. et al. (1972). “Effect of coccidiosis on pigmentation in broilers.” Br. Poultry. Sci. 13:577-585

- Marusich, W. et al. (1972). “Effect of coccidiosis on pigmentation in broilers.” Br. Poultry. Sci. 13:577-585